Classicism, Mannerism and the Baroque: Art and Patronage in Europe

This unit looks at the way in which artistic change was shaped by the desires and aspirations of patrons on the one hand, and by the artists' own moulding of the wishes of the patrons, on the other. The focus of the unit is on Italy, and above all, Florence and Rome. First of all, these cities were the seed-bed of the development of the "High Renaissance", which was linked with the language of classicism. Secondly, the two styles evolving out of classicism - mannerism and the Baroque - were no less Italian in their original creative impulses. Mannerism originated in Florence and was exported by patrons and artists to the rest of Italy and much of Western Europe. Similarly, the Baroque was a movement which originated very clearly in Rome in the first decades of the seventeenth century and was gradually expanded from there.

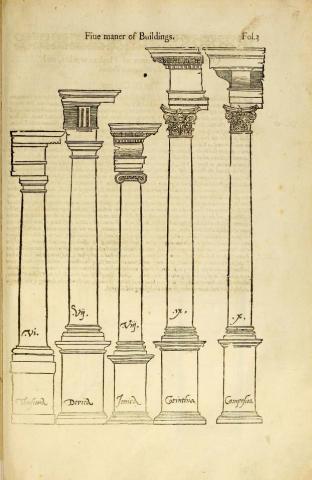

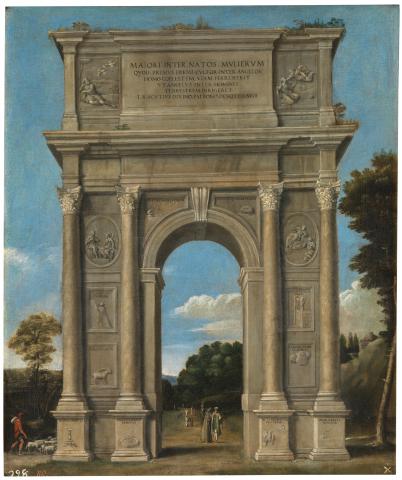

What do we mean by classicism in an artistic context? Essentially a collection of rules – supposedly derived from ancient authors or the models of antiquity – which provided prescriptions for subsequent art and architecture. Beyond this copying of antique architecture and art, however, there was something less easily definable, but possibly more powerful – a set of assumptions about the wider meanings of classical society and culture for the present. Classical philosophy, moral values and political assumptions were potentially attractive to humanist-educated patrons, who wished to see these expressed in the art that they commissioned. In both cases what was attractive was the legitimizing connection, the implied link between the present-day elites and an idealization of Roman republicanism or imperial grandeur and its values of unchallenged authority, order, peace and prosperity. (David Parrott)

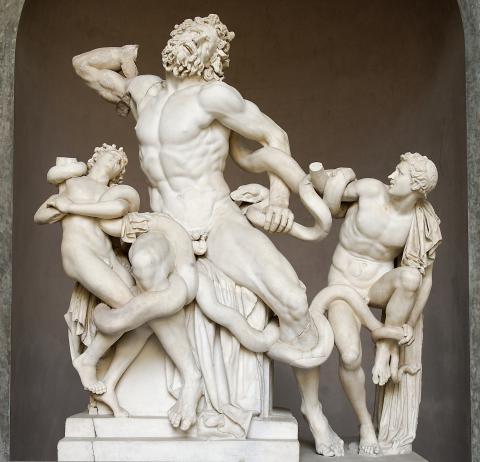

The key artistic development of the 15th century, with origins in Florence, Rome and Venice. Artistic classicism was part of a larger “Humanist” project to revive the classical past, pre-eminently the intellectual and cultural property of the Italian states, who saw themselves as direct heirs to Republican and Imperial Rome. Fifteenth-century Italian painters, sculptors and architects sought to adopt the stylistic conventions of a Roman past, facilitated by the survival of plentiful examples of classical buildings and sculpture, and by the re-editing and re-imagining of classical treatises on architecture such as Vitruvius’ De Architectura (The Ten Books on Architecture). Examples of classical painting were less readily available, but contemporary humanists and painters drew attention to the writings about classical Greek painters such as Apelles, celebrated in the work of Pliny, or the fifth-century BC rivals Zeuxis and Parrhasius. Celebrated in these painters was their apparent power of verisimilitude, their ability to depict a reality so lifelike as to deceive the spectator. But they had also surpassed that reality through creative imagination to achieve idealizations of beauty based on harmony, proportion and integration. The Renaissance artist was thus presented as more than a highly-skilled craftsman, realistically depicting the surrounding world. The creative insight possessed by the outstanding artist, shaped by these classical conventions of style and composition permitted the realization of ideal beauty and perfection of form (David Parrott).

If mannerism was something of an artistic connoisseur’s indulgence, the transformation of classicism brought about by the artists and architects of the baroque was an altogether larger-scale and more all-embracing phenomena.

This was an art for the Church, and it had three concerns:

- To find art forms that would seize the attention and emptions of the Catholic population – offering them art that would communicate intensely and directly through scale, grandeur, emotional directness and intensity.

- To develop an art that would glorify and celebrate the achievements of a resurgent catholic church, rising from the ashes of its apparent defeat by Protestantism in Northern Europe, to take on the mantle of a global religion whose adherents were far more numerous than the church of pre-reformation Christendom.

- To provide opportunities for the Papal families to stamp a distinctive artistic mark on the city where the family intended to build and maintain its career and status after the death of the Papal head of the family.