Week 6 - Imperial Connectivity

Essay: How closely interconnected was the Achaemenid Empire?

Presentation 1: Memphis Customs Account

Presentation 2: Black Sea Hoard and Jordan Hoard

Introductory:

A. Kuhrt, The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period (2007), 730-762 (excellent collection of sources)

P. Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander 357-387

General:

P. Briant, ‘From Sardis to Susa’, in Kings, Countries, Peoples (2017), 359-374.

H. Colburn, ‘Connectivity and Communication in the Achaemenid Empire’, Jounral of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 56 (2013), 29-52.

W. Henkelman, ‘Imperial signature and imperial paradigm’, in Die Verwaltung im Achämenidenreich, eds. B. Jacobs et al (2017), 45-256 – no need to read all of it; connectivity discussed in early part of the paper.

Memphis Customs Account:

P. Briant, ‘A customs register from the satrapy of Egypt in the Achaemenid period’, in Kings, Countries, Peoples (2017), 377-414.

Brief and pungent comments also in N. Purcell, ‘A view from the customs house’, in W.V. Harris (ed.), Rethinking the Mediterranean (2005), 200-234.

Coin hoards:

C.M. Kraay and P.R.S. Moorey, ‘A Black Sea Hoard of the Late Fifth century BC’, Numismatic Chronicle 141 (1981) 1-19

C.M. Kraay and P.R.S. Moorey, ‘Two fifth century hoards from the Near East’, Revue numismatique 1968, 181-235.

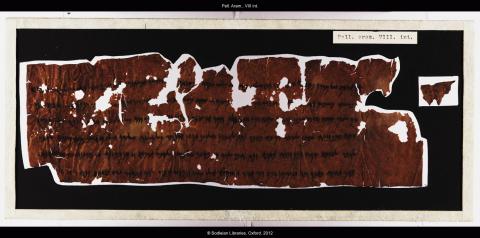

The original contents of the “Black Sea” hoard consisted of at least 102 silver coins (78 of them now in the Ashmolean), of which some 60% had been test-cut and some 39% were incomplete fragments of coins that had been deliberately broken apart with a chisel or knife. The hoard also contained a large quantity of uncoined silver. The part of the hoard which ended up in the Ashmolean includes 38 uncoined silver objects (ingots, “Hacksilber” and miscellaneous objects); the hoard is reported also to have contained more than 300 further “unornamented small fragments of silver”. The coins in the hoard mostly date to the mid-fifth century BC and the hoard seems likely to have been buried c. 420 BC. (The single coin from Paphos in the hoard is now generally dated c. 400–370 BC, but this seems too late for the rest of the hoard’s contents.)

The attribution of this hoard to the Black Sea region (proposed by Kraay and Moorey (1981)) rests solely on the presence of the large number of coins in the hoard attributed to the city of Sinope, on the Black Sea coast of Turkey. This attribution is problematic, as pointed out by F. de Callataÿ (2003: 271-2) (cf. Alram 2012 (71), suggesting that any doubts about this hoard's authenticity are 'unfounded'). No other contemporary hoards from the Black Sea region include this volume of Athenian owls, or of coins struck on the south coast of Anatolia; nor do we have other “mixed” hoards of coined and uncoined silver from this region. de Callataÿ prefers to attribute this hoard to the Levant or Egypt, where “mixed” hoards of this kind are very common, and his reasoning was accepted by Peter van Alfen. The large number of coins of “Sinope” in the hoard might argue against a provenance in the Levant; but the attribution of this coin-series to Sinope is far from certain.

Hoards of this type predominantly date to the fifth century BC; they become much rarer in the late fifth and fourth century, with the beginning of large-scale coin-minting by the Phoenician cities. For a fourth-century example, see e.g. Gitler's 2006 article.

Key Bibliography:

Publication: C.M. Kraay and P.R.S. Moorey, ‘A Black Sea Hoard of the Late Fifth century BC’, Numismatic Chronicle 141 (1981) 1-19 and Coin Hoards 1.15.

Discussion and parallels: P. van Alfen, ‘Herodotus’ “Aryandic” silver and bullion use in Persian-period Egypt’, American Journal of Numismatics 16/17 (2004-5), 7-46.

For a taste of the issues (and controversies) surrounding the iconography and production of the King-Archer coinages, see M. Cool Root's article, and in more detail, C. Tuplin, 'The changing pattern of Achaemenid Persian Royal Coinage', in P. Bernholz and R. Vaubel (eds), Explaining Monetary and Financial Innovation 2014), 127-168.

![Image for BSH1: Silver didrachm of Segesta (Sicily) [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045153o.jpg?itok=NRVsscQN)

![Image for BSH2: Silver octadrachm of the Bisaltai (Thrace), fragment, c. 465 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.2 (SNG Ashmolean III 2244). [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045154o.jpg?itok=YkjGSzAM)

![Image for BSH3: Silver tetradrachm of Akanthos (Chalcidice), fragment, c. 470 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.3 (SNG Ashmolean III 2201). [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045155o.jpg?itok=uQ5MVM2_)

![Image for BSH4: Silver tetradrachm of Athens, c. 450–425 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.7. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045156o.jpg?itok=utA1G1CT)

![Image for BSH5: Silver tetradrachm of Athens, fragment, c. 450–425 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.16. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045157o.jpg?itok=Q2BNZEAJ)

![Image for BSH6: Silver siglos/drachm of “Sinope”, uncertain mint (“Class A”), perhaps c. 450–425 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.25 (SNG Ashmolean IX 233). [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045158o.jpg?itok=PZvK_j8E)

![Image for BSH7: Silver siglos/drachm of “Sinope”, uncertain mint (“Class B””), perhaps c. 450–425 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.50 (SNG Ashmolean IX 258). [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045159o.jpg?itok=U1_w-VzG)

![Image for BSH8: Silver stater of Soloi (Cilicia), c. 440–420 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.58 (SNG Ashmolean XI 1790). [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045160o.jpg?itok=__bL81Qr)

![Image for BSH9: Silver stater of King Onasi-, Paphos (Cyprus), probably c. 450-420 BC. Kraay and Moorey 1981, no.60. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045161o.jpg?itok=4GhfktOL)

![Image for BSH10: Silver siglos, probably minted at Sardeis. Mid-late 5th century BC. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045162o.jpg?itok=r4TwUkfz)

![Image for BSH11: Silver ingot (ovoid). ["obverse"]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045163o.jpg?itok=W0rJzSLh)

![Image for BSH12: Silver bar-ingot (cut down). [View 1]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045164o.jpg?itok=uV5L_paH)

![Image for BSH13: Silver bar-ingot (complete). [View 1]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045165o.jpg?itok=JBleODSW)

![Image for BSH14: Silver strip. [View 1]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045166o.jpg?itok=eTPLk80Z)

![Image for JH1: Silver stater of Messana (Sicily), c. 488–481 BC. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045167o.jpg?itok=kAUwU2dM)

![Image for JH2: Silver tetradrachm of Akanthos (Chalcidice), fragment, c. 470 BC. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045168o.jpg?itok=9dSOnJfy)

![Image for JH3: Silver stater of Thasos, fragment, DATE. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045169o.jpg?itok=Pe9ePBSY)

![Image for JH4: Silver tetradrachm of Athens, fragment, DATE. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045170o.jpg?itok=YepFLNt6)

![Image for JH5: Silver diobol of Miletos (Ionia), DATE. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045171o.jpg?itok=DRXI6ntc)

![Image for JH6: Silver stater of Paphos (Cyprus). [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045172o_0.jpg?itok=VG5K88hY)

![Image for JH7: Silver double-shekel of Tyre (Phoenicia), DATE. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045173o.jpg?itok=hNuy_pA2)

![Image for JH8: Silver bar-ingot, cut down to size from a larger bar. [View 1]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045174o.jpg?itok=ExiG4VB4)

![Image for JH9: Silver ingot cut from a rod or bracelet. [View 1]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045175o.jpg?itok=9GSnwGSw)

![Image for T5: Gold stater, so-called “Croesid”, struck at Sardeis after 547/6 BC. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045197o.jpg?itok=YsrMSA6q)

![Image for T6: Silver stater, so-called “Croesid”, struck at Sardeis after 547/6 BC. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045198o.jpg?itok=b3jmL2CM)

![Image for T18: Silver siglos, “King half-length” Carradice Type 1. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045181o.jpg?itok=auvTJ8Kh)

![Image for T19: Silver siglos, “King shooting” Carradice Type 2. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045182o.jpg?itok=8QV9kyE5)

![Image for T20: Silver siglos, “King with bow and spear” Carradice Type 3. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045183o.jpg?itok=W3SNRrwv)

![Image for T22: Silver 1/6 siglos, “King with bow and dagger” Carradice Type 4. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045185o.jpg?itok=Fum6eOWH)

![Image for T24: Gold daric, “King with bow and spear”, Carradice Type 3. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045187o.jpg?itok=zf1EwXIU)

![Image for T25: Gold double-daric, “King with bow and spear”. Carradice Type 3. [Obverse]](https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/sources/0045188o.jpg?itok=xU1k67fq)