The Protestant Churches: Ideals and Institutions

When Martin Luther began to put forward new ideas about how human beings were saved, he sparked a religious and political movement known to us as the Reformation. Protestant churches followed his central principles of justification by faith and the supremacy of the scriptures, but these ideals found expression in different forms of church life. Lutheran and ‘Reformed’ versions of Protestantism developed, often in tension with one another as well as with the Catholics. This unit explores the ideas which underpinned the Protestant movement in its different forms and examines the ways in which those ideas affected the practice of religion, politics and diplomacy in the generations after Luther’s dramatic stand against the Roman Catholic Church (Sarah Mortimer, July 2018).

Protestant leaders were often depicted in sober, plain academic dress and sought to emphasise their scholarly qualities by holding books. They knew that the doctrine of scripture alone could give power to laypeople to interpret scripture for themselves so they wanted to make sure that only properly educated male scholars could pronounce on the Word of God. (Sarah Mortimer)

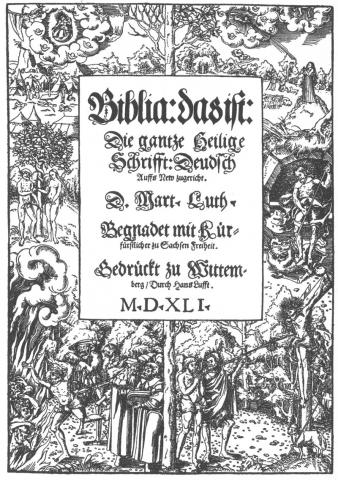

The Protestant leaders wanted to bring the Bible to the people in the vernacular and one of Luther’s earliest projects was a German translation of the Bible. But they swiftly recognised the need for educational institutions where Protestant doctrines could be taught and defended. The sixteenth century saw a wave of new colleges and universities which were intended to create a new, learned elite who could serve both the state and the church.

(Sarah Mortimer)

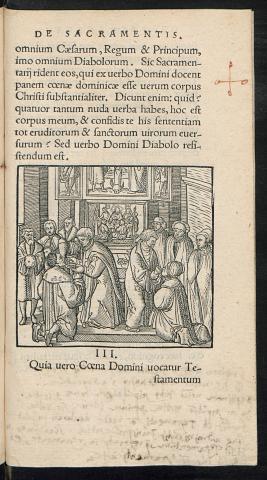

From the early 1520s, Luther attacked the papacy as Anti-Christ and his theology was often bound up with a very hostile stance towards Rome. This helped to simplify his message and make it attractive to people in Germany who were often already antagonistic towards Rome. As the Protestant movement fragmented, fear of Catholicism helped to hold it together. (Sarah Mortimer)