Museum Wormianum, 1655

Commentary

Jump to: Commentary • In Depth • Images 2-3

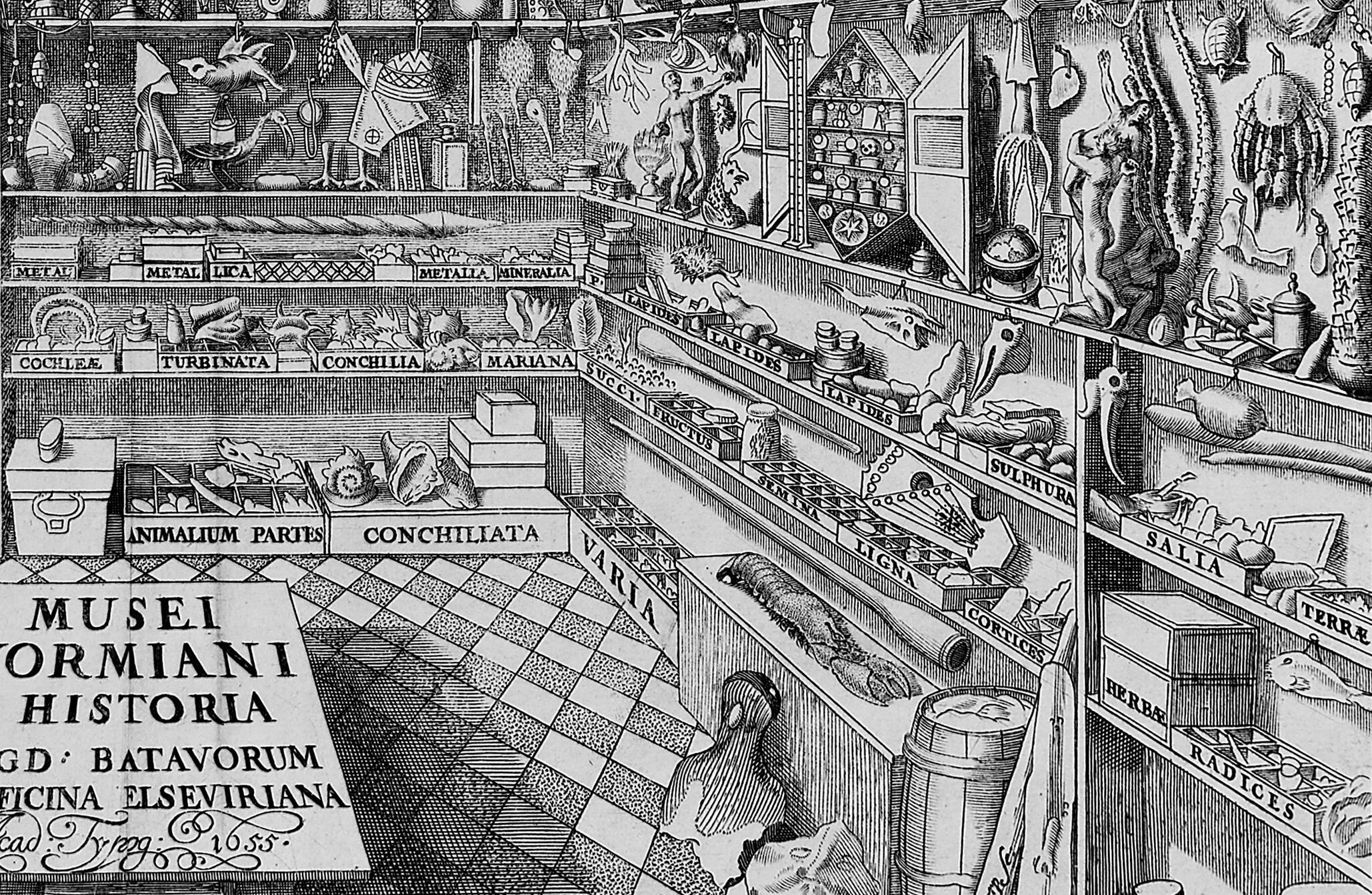

Image 1. Frontispiece to Ole Worm's Museum Wormianum (Leiden: 1655). Engraving by G Wingendorp; published by Isaac Elzevier. Date and place of production: Leiden, 1655. Dimensions: height 278, width 358. Inscriptions: Titled in lower centre: "MUSEI / WORMIANI / HISTORIA / LUGD. BATAVORUM / EX OFFICINA ELSEVERIANIA / Acad. Typog: 1655". Signed in lower right: "G. Wingendorp sc:". Source: BodleianLibrary, shelfmark Ashm. 1713. See Museum Wormianum online.

One of the most famous early museums was that of Ole Worm (1588-1654), a Danish professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen. According to one contemporary account,

many royal persons and envoys visiting Copenhagen ask to see the museum on account of its great fame and what it relates from foreign lands, and they wonder and marvel at what they see.

Jens Lauridsen Wolf, Encomion regni Daniae (Copenhagen, 1654), 356.

Worm's museum achieved even more fame due to the posthumous publication of the Museum Wormianum (1655), which was both a catalogue of the museum and Worm's contribution to natural history. Most famous of all was the frontispiece fold-out engraving, which presented Worm's collection in one room (Image 1). Worm seems to have emulated the example set by the cabinet of the apothecary Ferrante Imperato in Naples, which he certainly visited.

Worm had an extensive collection, not all of which was housed in the display room. After his death, it was purchased by Frederic III (1609-1670), the King of Denmark and Norway, whose personal physician he was. It hence lay at the foundation of the Royal Danish Kunstkammer, itself the basis of the Danish modern museums. Although Worm's collection was disbanded, certain pieces have been identified as belonging to the original museum.

The famous frontispiece strikes you as being, in many ways, completely different to a modern museum. Although museums differ in shape, size and layout, they rarely display so many objects in such small space. Indeed, upon looking at the image the eye is assaulted by the huge amount of objects crammed into every nook and corner of a room that was no more than 10 m squared. Schepelern, the foremost authority on Worm, has counted no less than 215 objects in the image. The quantity is meant to overwhelm, eliciting an emotional response in the viewer. We are rendered uneasy, but also curious - what are all these objects? What is their story, and why are they positioned where they are?

At first glance, the setup seems completely disorderly. You would not expect to see stuffed birds next to statues or a musical instrument next to pieces of wood. Once the eye accustoms to the jumble, it can, however, identify some method to the madness. The catalogue of the Museum Wormianum helps in the sense-making process: for instance, the mineralogical collection on the third shelf from the bottom is organised in accordance with the first book of the Museum Wormianum (on fossilia, or things extracted out of the earth): starting from earths (terrae), moving to salts, sulphurs, stones (lapides) and metals. The presence of the boxes named 'P.' and 'Mineralia' is less comprehensible; the mineralia may refer to objects fitting the restrictive sense of the word 'mineral', which, Worm tells us, refers to things extracted out of mines.

The second shelf reflects the second book, on plants, up to the box named 'Mariana' (probably a misspelling of 'Marina' - sea plants). This is a less impressive shelf, but we should not forget that Worm also had a botanical garden, which presumably would have offered more enlightening specimens of plants.

From there on the boxes reflect the fourth book on animals. But the relatively orderly structure breaks down beginning with the box titled 'Varia', which seems to be a waste basket for anything-else-that-doesn't-fit-in-the-categories (but can fit in one box). The sense of mystery is compounded by the closed boxes and barrel laying in the right foreground - what do these contain?

The upper right shelves (above the minerals) and the right wall seem to continue the investigation of the animal kingdom in somewhat orderly fashion. Birds, for instance, are generally set in the front area, while reptiles and small exotic animals (like the armadillo) are hung on the wall. Some parts of larger animals (like stags' or reindeers' antlers) are found on the left wall.

An important object in many cabinets of curiosities of the era was the 'unicorn horn', which was particularly coveted and could fetch astonishing prices on the open market. Worm is now recognised as one of the first scholars to have demystified this object, identifying it with the horn of the narwhal fish. In the Museum Wormianum he discussed the narwhal horn at length and provided images of the fish itself.

In the museum itself, we can identify two unicorn horns: one that looked like the traditional unicorn horn as well as a skull of a narwhal with the horn itself. Worm probably showed his visitors first the de-contextualised horn and then the skull, thus persuading them of the true origin of this object.

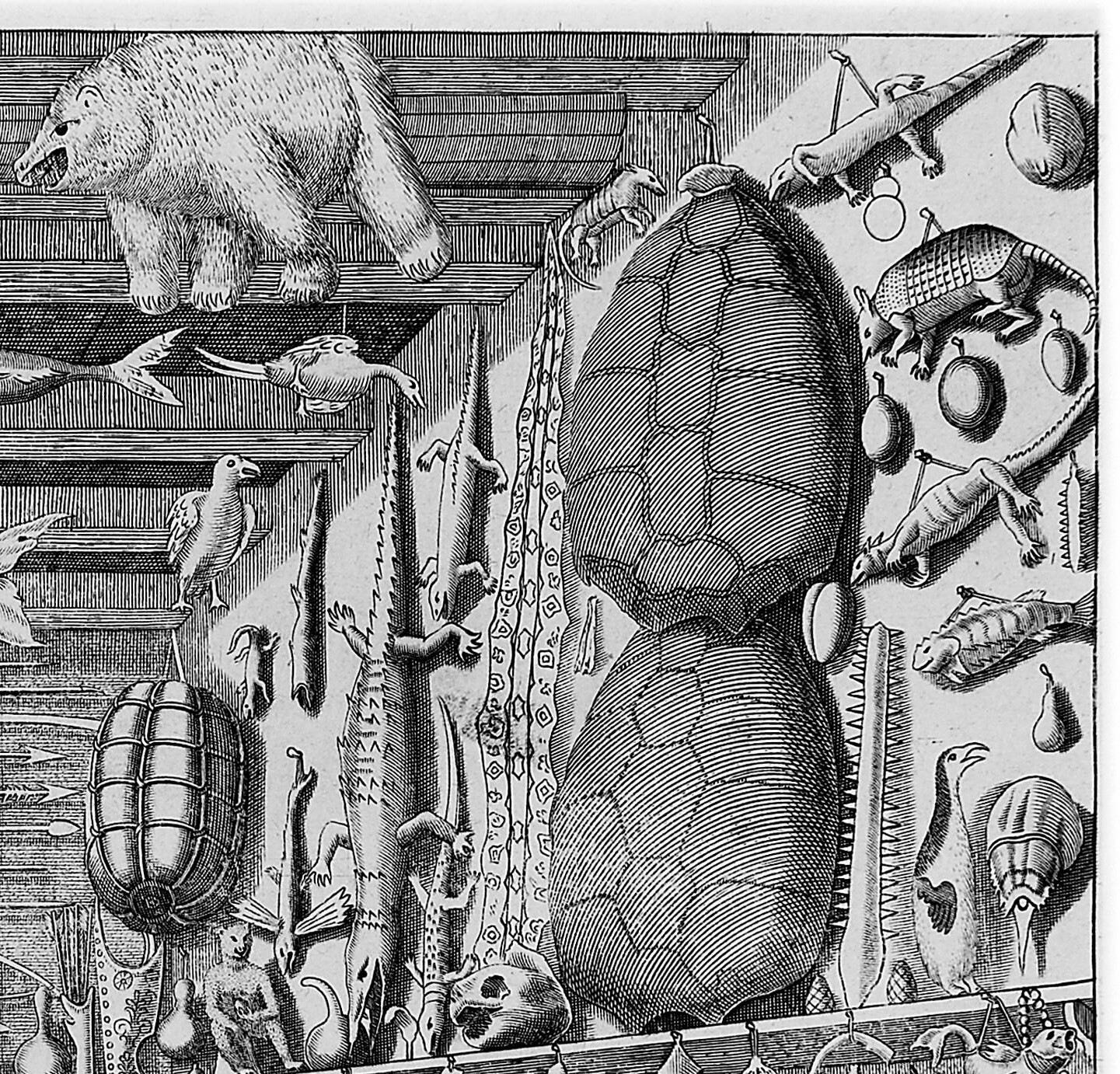

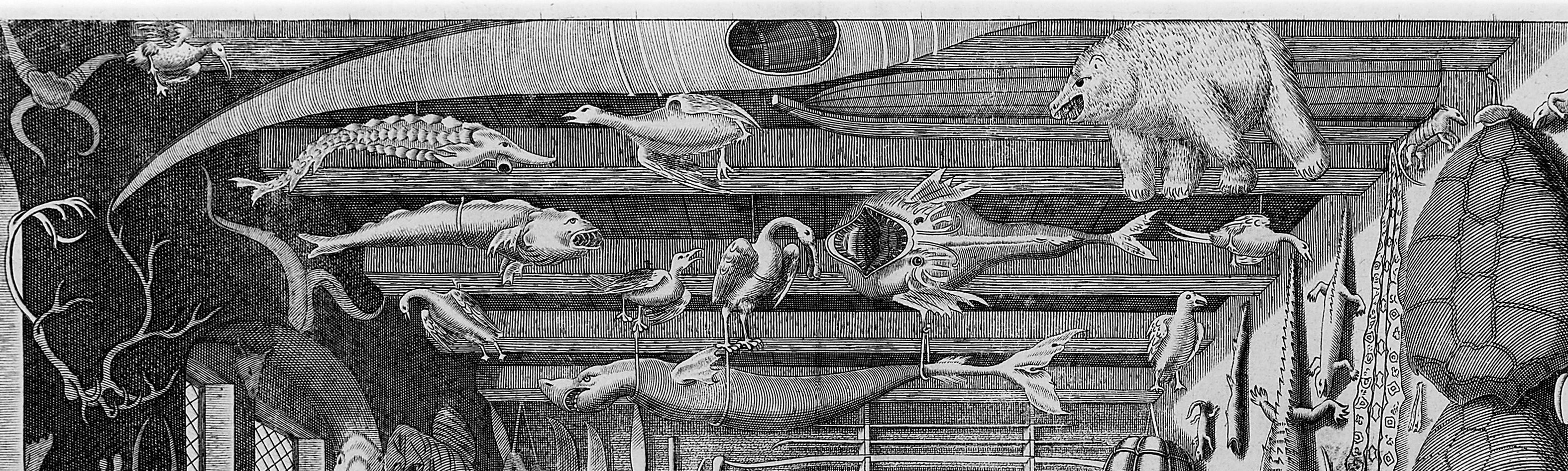

However, the most impressive animal specimens are hung on the ceiling. This positioning is a nod to the Museum of Francesco Calzolari (1521-1600) in Verona, which similarly featured such large-sized specimens on the ceiling.

The ceiling is a strange place, where you can equally find birds, fish, a bear cub and even a canoe. Why do the fish swim on the ceiling? A reasonable explanation is that these are all stuffed animals and, being three-dimensional, it made sense to place them there. Yet there may be more to it than this. While the visitor's eye is almost inevitably first captured by the humanoid statue placed in front of the room, the jumble of objects everywhere makes it inexorably travel toward the ceiling, where other large specimens are situated. The size and the unlikely (and vaguely threatening) positioning of these provoke awe and wonder in the watcher, the more so as the seventeenth-century visitor was unlikely to be as familiar with a polar bear as we are today. The fish displayed are large and stuffed in such a way as to make them conform with the traditional concept of the 'sea monster': see, for instance, the fish with a huge mouth seemingly intent on 'eating' the visitor. These unusual fish, evoking the Leviathan and Jonah's whale, are displaced from their natural environment in a clear reversal of the old, settled world order, causing a mixture of fascination and fear in the visitor.

Worm has been praised for his collection of artificialia, that is, human-made products. The artificialia was a catch-all term for anything from ethnographical pieces to art, and in some cases, simply curiosities. The most striking object in the category (and perhaps the entire collection) is the statue of the man in front - except this was not a statue, but an automaton, a moving piece. This is clearly a wonder-producing object, whose role is not so much to illuminate, but to mystify. We are invited to contemplate the ability of human beings to create art that closely resembles nature.

Images 2-3: 'All things strange and beautiful', an installation by Rosamond Purcell, Geological Museum, Copenhagen.

It takes a certain suspension of disbelief to dream one's way back into a picture. Yet whenever I stared at the engraving, it was as if I were actually there, inside a day-lit room among so many mysterious and familiar things I might touch or even hold.

As I stare at the wide-angle depiction of Worm's narrow room, its walls and even its corners seem to unfold like a body splayed open for autopsy.

Rosamond Purcell, 'A Room Revisited', Natural History 113:7 (2004), 46-48.

In 2004, American artist and photographer Rosamond Purcell reconstructed Worm's famous frontispiece at the Santa Monica Museum of Art. The installation was later made into a permanent exhibit at the Geological Museum which forms part of the Museum of Natural History of Denmark, near the location of the original Museum Wormianum. The exhibition is described briefly in the accompanying video (more of a teaser), and articles elsewhere, including those at the University of Reading's Special Collections (May 2020), by Dawn Hoskin at the Victoria and Albert Museum (May 2015) and by Alison Meier at Atlas Obscura (April 2013). Read Purcell's own musings about her recreation of the frontispiece here (download NH113n07).

Credits: Georgiana D. Hedesan (Nov 2021).

Further reading.

G. D. Hedesan, “University Reform and Medical Alchemy in Ole Worm’s Museum Wormianum (1655)”, in Collective Wisdom: Collecting in the Early Modern Academy, eds. Anna Marie Roos and Vera Keller (Turnhout: Brepols, 2022), 85-106.

H. D. Schepelern, ‘The Museum Wormianum Reconstructed: A Note on the Illustration of 1655.’ Journal of History of Collections 2, no. 1 (1990): 81-6.