Morison's project

Exploration of the globe revealed there were more plants than those mentioned in the Bible and classical texts. Alphabetical lists of plants names and descriptions, or arrangements based on flowering time, habitat and plant use, aided cataloguing but were insufficient to synthesise botanical knowledge. Methods were needed that reflected mutual, observable similarities among individual species; order had to be brought to the plethora of plant names in circulation.

The classification system of Theophrastus, where plants were assembled as trees, shrubs or herbs, identified broad, habit-based groups, with variants of it persisting in botanical literature for nearly two thousand years (Morton, 1981). Other systems, focused on roots or leaves, were rejected. By the end of the sixteenth century, authors in the late-herbal tradition were starting to group similar plants in their works but the bases of these groups were often unexplained (Arber, 1986). For example, in the works of the Flemish physician and botanist Matthias de l'Obel (1538-1616) groups reminiscent of some plant families recognised today are seen, e.g., the cabbages, carnations and mints (Ogilvie, 2006: 44-46; Arber, 1986: 176-177).

In 1583, the Italian physician and botanist Andrea Cesalpino (1519-1603), Director of the Pisa botanic garden, published De Plantis Libri XVI and an explicit system of classification. Cesalpino’s system was based on the parts of the flowers and fruits (fructifications): ‘of the fructification grace has been granted to investigate the kinds of plants’. The first cut in Cesalpino’s scheme followed Theophrastus, grouping trees with shrubs, and undershrubs with herbs. Subdivisions within each of these groups made use of the number, position and form of the fruit and flower. However, despite its order and method, Cesalpino’s classification system was not taken up by other sixteenth-century botanists. Botanical focus once more became names and descriptions, rather than classification. For example, Gaspard Bauhin’s (1560-1624) Pinax Theatri Botanici (1623), the standard catalogue of the world’s known plants (c. 6,000 species) during the first half of the seventeenth century, the product of four decades of meticulous research, used an arbitrary system to group taxonomic names.

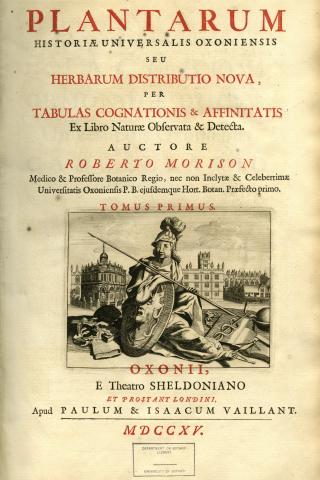

In the dedication to King Charles II at the front of the Hortus Blesensis (1669), Robert Morison, about to be appointed Regius Professor of Botany at Oxford, announced a new and original method of plant classification: ‘The new method is being given by nature to me, I only (boast) observe: none but my own to this point detected the contemporary world’s cradle’. He goes on to observe that ‘if you [Charles II] deign to consent to covenants to me: I promise your Britain an exact method (which is natural), whereof she could boast of botany in the future, as Italy, France and Germany, in the last century, without a method, were praised in the science of botany’. In Morison’s Dialogus inter Socium Collegii Regii Gresham dicti et Botanographum Regium (1669), a thinly-veiled dialogue between Morison and John Ray (1627-1705) published with Hortus Blesensis, Morison asserts ‘I admit, I have observed this method: it is, of all the things that have ever been produced, the best and, most certainly, by nature’. Morison did not produce an explicit description of his method, but made the point that the features important for classification were not to be found in either the properties of plants or their leaves but in their flowers and fruits.

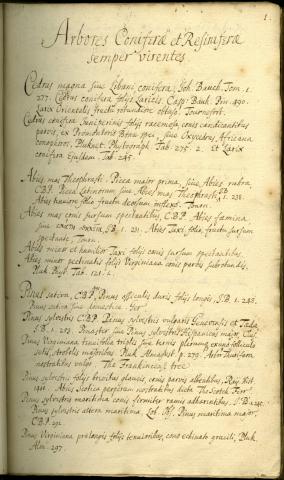

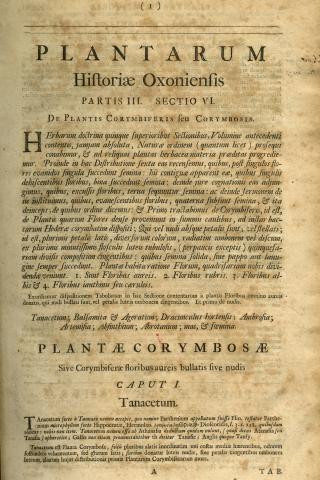

The principles of Morison’s method were not disclosed until he published Plantarum umbelliferarum distributio nova (1672: Preface): ‘while method is the soul of all doctrine: so we both arrange the umbellifers, and all plants in a promised overall process. The marks of kinds by the essential similarities of the seeds are sought, by tables of kinship and affinity that dispose the plants. Specific differences from the other parts have meaning, namely the root, leaves and stem, aroma, flavour, colour are considered, for several kinds and each included form. Thus, different forms are recognisable, under intermediate kinds. Under the last intermediate kinds its essential, invariable marks serve to distinguish them. This is the pattern from the beginning, from the very nature of the races, I had first observed’.

In 1675, Morison claimed that after ‘his arduous and long observation, discover’d a more easie and Scientifical Method of knowing Plants out of the Book of Nature, according to the different forms of their Flowers, Seeds, and Seed pods, than hath ever yet been published’ (Morison, 1675: 372). However, the full extent of Morison’s system was not made known until 1720, with the publication of the anonymous Historiae Naturalis Sciagraphia in Oxford, which is usually attributed to Jacob Bobart the Younger.

In the Preface to Volume 2 of the Historia, published in 1680, Morison explained that his method came from his study of the ‘Book of Nature’, whilst its focus on fruits had divine authority from the first chapter of Genesis: ‘And God said, Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself, upon the earth’.

References

Arber A 1986. Herbals. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Morton AG (1981) History of botanical science: an account of the development of botany from ancient times to the present day. Academic Press, London.

Ogilvie BW 2006. The science of describing. Natural history in Renaissance Europe. Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press.

Morison R 1675. A Proposal to Noblemen, Gentlemen and others, who are willing to subscribe towards Dr. Morison’s New Universal Herbal, ordering Plants according to a new and true Method, never published heretofore. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 114: 327-328.