Modelling the heavens? Astronomical instruments and mechanical clocks

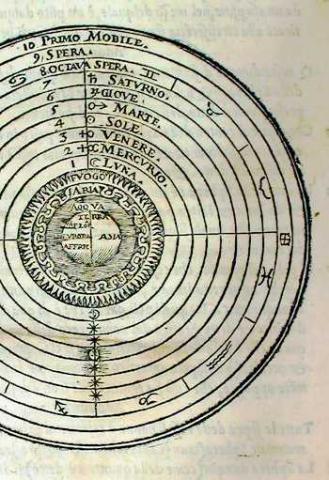

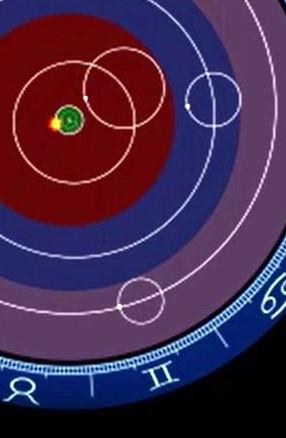

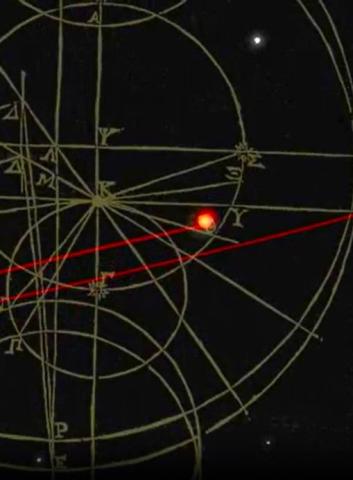

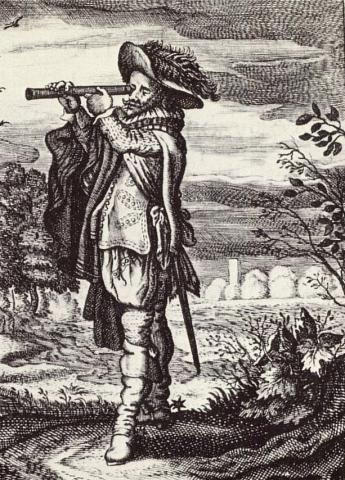

At its most literal, a ‘world view’ is a cosmology, a theory about the natural world as a whole. In 1543 – very near the mid-point of our period – Copernicus introduced a new cosmological theory which turned the received world view inside out. The sun, he argued, rather than the earth, was the central body around which the entire system turned. Why did Copernicus favour this new view? Answers to this question require some familiarity with received consensus. And why was his alternative not adopted immediately? To this question, there are three main answers. First, empirical support for his view was lacking: Tycho Brahe exhausted the capacity of naked-eye observation without finding such evidence, and it was only Galileo's telescope which first revealed empirical support for Copernicanism in 1610. Second, Copernicus’s system was based on flawed premises deriving from the previous system which were only removed by Kepler in 1609-19. Third and most importantly, a new physics was needed before a coherent alternative to the synthesis of Aristotelian physics with Ptolemaic cosmology could be created. Galileo laid some of the groundwork for this new physics during the 1630s, but the full solution was not found until Newton published his Principia (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) in 1687. Our entire period can therefore be characterised as one in which the old world-view was in disarray and no entirely satisfactory alternative had been provided. Comprehending the competing explanations of planetary motion is not something which history students are typically required to do. Thankfully, the internet is now full of visual aids and animations which ease the comprehension of this important topic. The purpose of this unit is to assemble some of these aids and to furnish them with a minimum of explanatory commentary.