Fanny's Writings

Fanny’s writing demonstrates not only literacy but also talent. Her son George remarked,

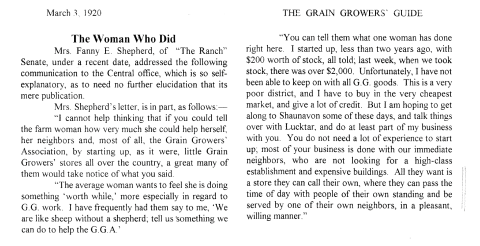

Mother amazed us all. Within three or four years of her arrival in Canada, she was writing a series of articles for The Grain Growers’ Guide called ‘Mother’s Hens.’ These were chatty little stories on how to set hens and perform the many other little farm chores that were a woman’s lot on the prairie farm. With her reputation as a poultry authority well-established, she took to a wider field, that of public speaking. She gave the leading address to the Women’s Section of the Grain Growers’ Convention at Moose Jaw. The Free Press Weekly reported this talk with the heading: ‘Hens should cackle all winter, says pioneer poultry raiser of Saskatchewan.’ (Shepherd, 46)

Fanny wrote a regular column called "Mother's Hens" for the Grain Growers’ Guide (GGG), a journal published from 1908-1928 for the Prairie Grain Growers’ associations, along with several short stories that were published in the Guide, the Nor’-west Farmer, and the regional, British temperance magazine, Onward.

In Fanny's writing, we see the ordinariness and everydayness as borne out generically through her 1) how-to literature, 2) short fiction, 3) political pieces, and 4) letters to her son, Geoff, when he was a soldier abroad. Raising chickens and explaining her methods in a beguiling and matter-of-fact way, Fanny's writing reveals the innovative ways women harnessed the soft power of the literary in popular journals and magazines. These writings are entertaining and instructional and evidently written by women for women.

We are interested in how far this might be a new form being developed by early twentieth-century women writers, the hybrid/non-fiction "how-to" literature, e.g. Mother's Hens, often appearing in little magazines. Other examples are Mary Burrill's "They That Sit in Darkness" (1919) and Marie Stopes's play Vectia (1923).

With regard to Fanny’s writings, we are interested in the wider literary networks in which they can be situated due to their investment in articulating women’s experiences of everyday life. When viewed in this way, Fanny becomes part of a vast network that takes in writers from the pioneer writers Laura Ingalls Wilder and Willa Cather to the Iowan modernist Susan Glaspell and New England’s Mary Wilkins Freeman; from ‘classic’ Modernists Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield to Southern women writers Flannery O’Connor and Alice Walker; and many more, all linked by their explorations of how far the written word could convey the qualities of everydayness without the need to make them exceptional. This literary context of the project is framed by recent scholarship by Rita Felski, Toril Moi, and others.