Catholic Reform

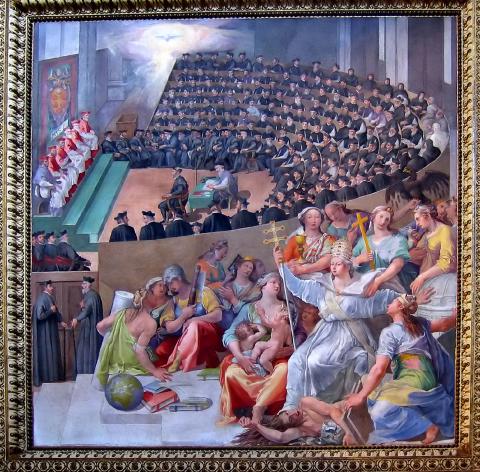

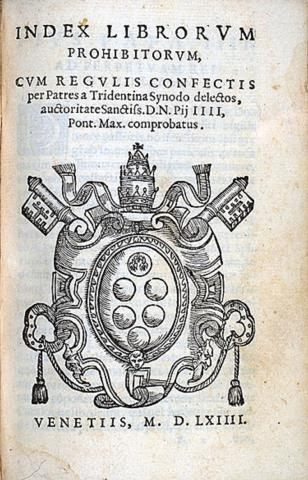

This unit considers how the Catholic Church itself, and the religion which it espoused, changed over the course of the early modern period. For sure, some of that change came in reaction to Protestant critiques and initiatives, but how much? Some reformist currents already circulated within the Church before Luther and evolved in parallel to his career, but their impact is hard to measure. Then there was the great Church council which met at Trent between 1545 and 1563 defining Catholic doctrines, often for the first time, and produced guidelines for reform.

But was the Church after Trent noticeably different from that before Trent and, if so, in which ways? Historians have traditionally looked for answers to this question in the ways the Council's decisions were disseminated amongst the faithful and enforced, but also in the activities of popes and particular reformers: how far did those individuals direct a programme of spiritual renewal? What were their objectives? What resources did they have to draw upon? How far did others follow them and why?

Then there is the changing nature of Catholic material culture: how did ordinary Catholics understand them and how far did they embrace them in their own lives, possessions, and routines? What role did Catholic missions play in European overseas expansion and in European encounters with other cultures? What about the Church's impact on education, not least through the new network of Jesuit colleges which sprung up all over Europe).

A final area within this topic is the place of Rome – the Sacred City – itself: how far did it emerge as a model city for a new reformed religion, a site for codifying official devotional practices and inculcating the cults of saints and relics, where monumental buildings and decorative programmes visualized and glorified the faith promoting Catholicism's 'Romanness'? (Miles Pattenden)

Christianity has always been a religion of saints and relics, but the Counter-Reformation saw important changes in how saints were understood, made, and used by the faithful. From 1588 a new Congregation, the Congregation of Rites, oversaw official processes of canonization in Rome – in theory now streamlined but often highly political affairs that lasted half a century or more.

But did the Catholic laity see saints in the same way as the Congregation's lawyers? The proliferation of relics and other holy items, including images, shows that saints and their relics was a vital part of lived Catholicism for many – one of the key ways in which they interacted with the sacred throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Much of the historiography of Counter-Reformation Catholicism focuses on particular individuals: the popes who oversaw the creation of a new catechism, breviary, and missal, and who directed Church resources into defence of the Faith and the evangelization of new peoples; bishops who reformed their dioceses and facilitated a spiritual and pastoral re-flowering; reformers who founded new religious orders or distant missions on foreign soil. But how much of this is simply 'Great Men's' history? How might we integrate the well-known stories about these particular individuals with a more balanced appreciation of Catholicism's changing role in the lives of an ever-more diverse laity?

One of the major characteristics that distinguished Catholicism from Protestantism in this period was its remarkable material production. Holy objects freighted with symbolic and emotional meaning abounded in early modern Catholic life. But what exactly did they mean to those who used them? How did they understand and cherish the aesthetic and theological qualities of a little wax Agnus Dei or a grand golden monstrance? What does the proliferation of such items in diverse locations across Europe, and even the globe, tell us about the men and women who commissioned, created, and consumed them – their values and beliefs but their understandings of ownership, community, and identity as well?

The Catholic Church had been at the forefront of education in medieval Europe, but its role developed significantly in the sixteenth century in several ways. First, through the creation of a new seminaries which were intended to train priests more intensively in the catechism they were supposed to transmit to the faithful; secondly, through a wider network institutions, in particular Jesuit colleges, which educated the laity as well as clergy, often in direct competition with the older universities. By 1773, when the Jesuit order was suppressed it ran over 800 such colleges across the globe from Mexico to Macao.

Catholicism's missionary character was another feature that distinguished it from contemporary Protestantism in this period. Indeed, Catholic missionaries spread out far and wide to take their faith to Africa, Central and South America, South- and South-East Asia, China, and Japan. What motivated these missionaries? But, just as importantly, how did they go about their efforts towards conversion? And what impact did their efforts, which included immersion in native cultures and languages, translating Christian texts and ideas, and even accommodating native ones, have on Catholicism – and, for that matter, on European society back home?

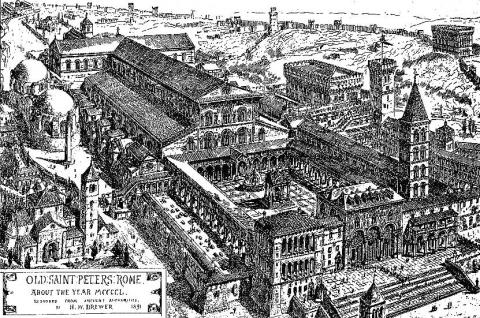

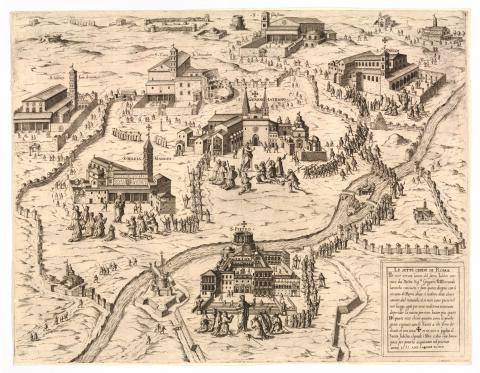

Rome was one of early modern Europe's greatest cities: a leading socio-religious and cultural centre which bounced back from the trauma of being sacked by mutinying Imperial troops in 1527 to become a cosmopolitan metropolis over over 100,000 souls. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century popes embarked on ambitious programmes to visualize their religion in monumental architecture, not least the great new basilica of St Peters which replaced the old medieval building and took over a hundred years to complete. But pilgrims also visited Rome’s other prominent churches to venerate miraculous icons and relics, to receive indulgences, and to hear mass. Jubilee years (1550, 1575, 1600, 1625, etc) were particularly important as times when the city flooded with such visitors: a holy door was opened in St Peter's and they could pass through to receive indulgence for their sins.