C5 - Worlds turned upside down

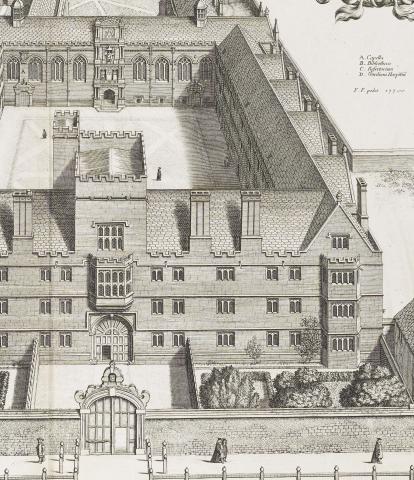

Between 1599 and 1637, Oxford created for itself a built environment worthy of a leading university, shaped to serve a set of statutes which was overhauled during these same years and published in 1636. During the second half of this period, much of continental Europe was experiencing an unprecedented crescendo of military conflict; and no sooner had Oxford put its house in order than it was engulfed in this chaos as well. By the time stability was restored in 1660, however, the intellectual priorities of the university had been transformed, particularly in the domain of natural philosophy. This coincidence raises a crucial question much discussed in the historiography of English science: did the political disruptions of the 1640s and 1650s retard or accelerate the intellectual transformations of this period? In pursuit of answers to this question, this unit explores some relevant evidence relating to Oxford, England and northern Europe more generally.

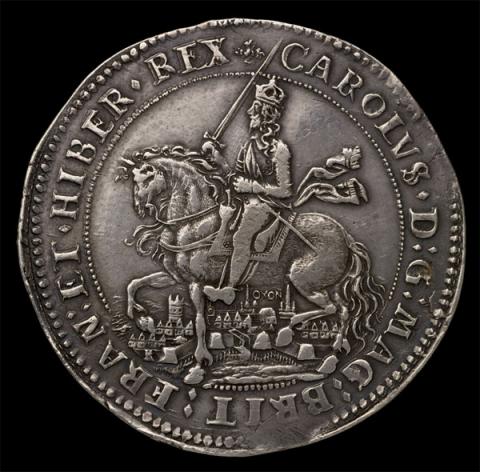

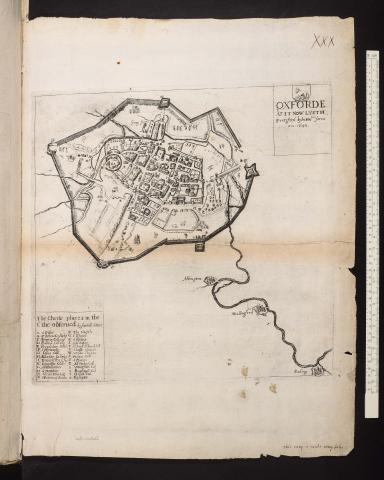

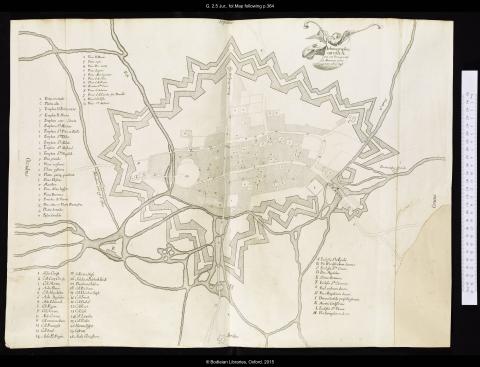

In Scotland, Ireland and England, the military conflict characteristic of this period was experienced most palpably during the civil wars which raged between 1642 and 1651. Between 1642 and 1646, Oxford was in the thick of the action, having been chosen as the capital of the royalist forces loyal to Charles I. The experience of Oxford during these years provides a vivid impression of the impact of war and upheaval on English learning more generally, as well as a local instance of the impact of military disruption on intellectual transformation experienced in various ways across much of Europe in this period.

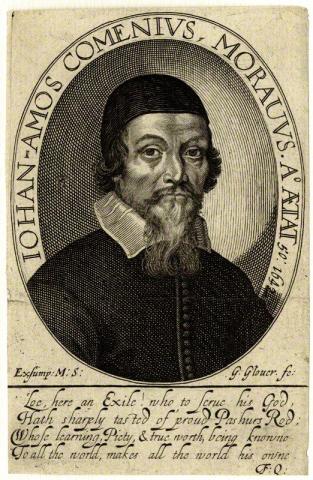

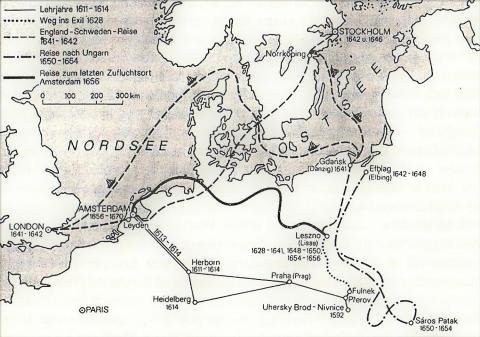

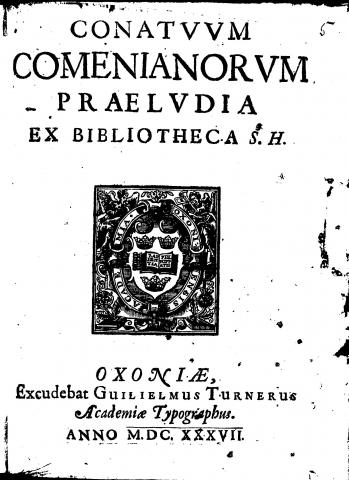

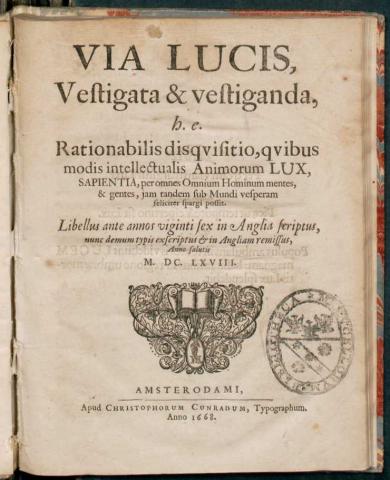

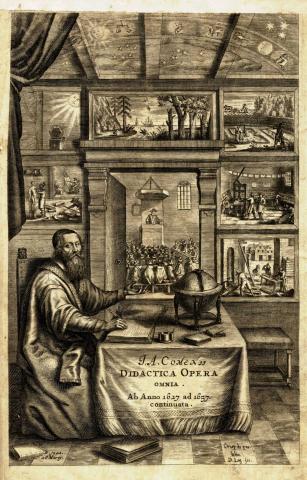

One characteristic manifestation of the intellectual culture of these years was the activities of a circle of intellectual reformers documented in the papers of the Anglo-German intelligencer, Samuel Hartlib (c. 1600-1662). Although normally discussed as a precursor to the Royal Society, this group was energized and indeed partly populated by the enormous military, political, confessional and intellectual disruption of central and northern Europe during these years. Nowhere is this link more evident than in the inspiration it drew from the writings of the Moravian pansophist and universal reformer, Jan Amos Comenius (1592-1670), who penned one of his most important programmatic works, the Via Lucis, during a brief sojourn in England in the winter of 1641-2. The activities and plans of these figures also impinged on Oxford: Comenius's first pansophic work was printed in Oxford in 1637; Hartlib's and his associates contributed to the critique of traditional university learning (discussed in the following cluster) and even proposed to transform the Bodleian Library into an 'Office of Addresse'.

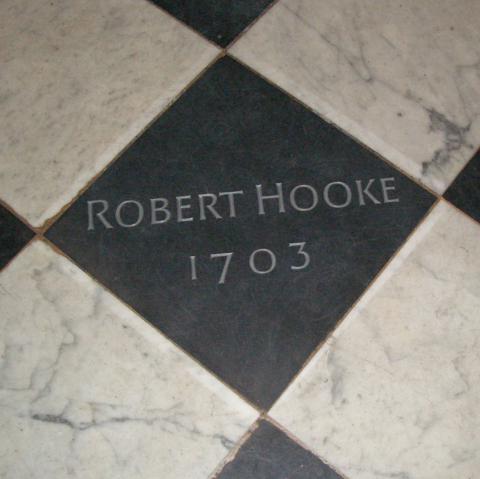

During the 1650s, the traditional curriculum of the English universities was subject to scathing criticism from such diverse figures as John Webster and Thomas Hobbes. By this time, however, Oxford had itself been debating these issues for some time, especially in a group centred around John Wilkins, the Warden of Wadham College. This cluster will piece together some of the scattered evidence for the activities and membership of this Oxford Philosophical Club, thereby setting the stage for a considerations of the debates between Webster and Hobbes, on the one side, and Wilkins, Seth Ward and John Wallis, on the other. The gallery of portraits of members of this group depicts them in their prime, typically many years later. The extent to which the seeds of these later accomplishments were sown in Oxford is a central issue for debate.