Rhodes and his legacies

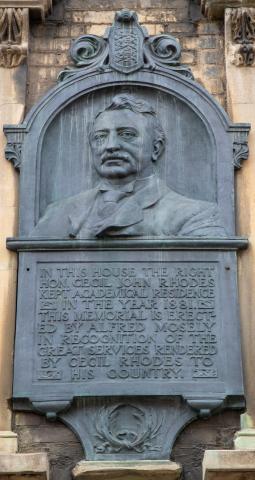

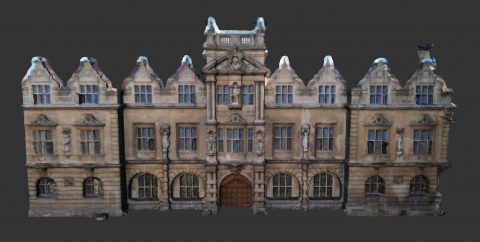

No one has more memorials in Oxford than Cecil Rhodes at Oxford. There are two busts and a portrait in Rhodes House, a portrait in Oriel College, a plaque in the Examination Schools, and another on his lodgings in Kind Edward Street. In the High Street, on top of the building which Oriel erected with his money, his statue is poised with those of Edward VII and George V (...). He would have appreciated all this, for he was obsessed by a desire for posthumous fame, and liked to be told his bust resembled that of a Roman Emperor.

Richard Symonds, Oxford and Empire : The Last Lost Cause? (1986)

Cecil John Rhodes (1853-1902) and his memorials are well known within Oxford and beyond. A nineteenth-century British imperialist, colonial politician, and mining magnate, Rhodes has become known both through his endowment of the Rhodes Scholarships as well as through debates over how his memorialisation is linked to legacies of British colonialism. Rhodes was a brutal and exploitative businessman and politician; in particular he and his policies drove an aggressive project of settler colonialism in Zimbabwe that precipitated rebellions and thereby war, famine, and death. With the 2015 movement ‘Rhodes Must Fall’, begun at the University of Cape Town (South Africa), Rhodes’s statue at Cape Town and his legacy became a focus of protests, a movement which spread also to Oxford and to the statue of Rhodes on the façade of Oriel College.

The protests have encouraged discussion and debate about endowments, memorialisation, and the legacies of colonialism. As William Beinart explains in his essay on Rhodes and his legacy, ‘Rhodes did an extraordinary amount in his short life. Hugely ambitious and driven, he made an impact in many different spheres. However, discussions in Oxford tended to personalise many historical developments and processes with which he was associated, but for which other people and groupings were significant agents.’ Beinart, who established the University of Oxford’s Centre for African Studies, concludes his essay by encouraging readers to continue to engage with the history of empire and memorialisation, writing ‘The statue should be made an object of debate and analysis;’ a way to understand, discuss, and criticise the British Empire.

Read more on the life and legacy of Cecil Rhodes